INDEX

Photo Essays

Myanmar - On the Circular

Afghanistan - Strengthening the Rule of Law

Sweden - Blue Gold

Talibé - The Least Favored Children of Senegal

Children of the Americas

The Georgia Files

A Life Displaced

Resiliance Comes in Many Shapes

Women Reconstructing a Country

Lomisoba - A Feast of Many Meanings

Chiatura - On the Manganese Trail

Wall Art & Online Training

Wall Art

Online Photography Training - Basic Photography for Peace Security and Development Monitoring

Booking

Prices include relocation to a place of choice. Up to 20-25 images are delivered in digital format to the client. Depending on intended use (commercial, print, wide distribution) changes may apply. All clients/models must sign the release. The price does include studio lights but not rent for a studio. Any additional expenses are covered by the client if nothing else is agreed. All photoassignments are subjected to discussion with the client. Materials are ready within 10-14 days (subejcted to changes depending on workload).

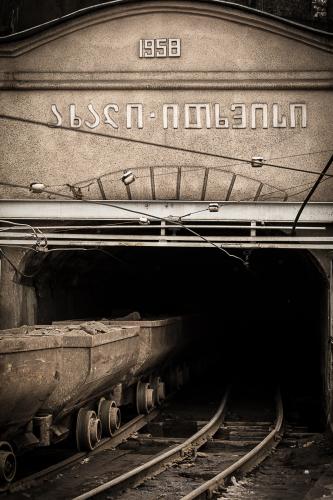

Chiatura

On the Manganese trail

No image can do Chiatura justice. As if taken from well-crafted fiction, the dystopian post-apocalyptic atmosphere is nothing short of ghostly. The monotonous humming of engines, the casual flight of dilapidated cable cars across the gorge, the whistling sound of mechanical movement and seemingly random explosions that echo throughout the valley – it all bears witness to life in spite of time. Wedged into the Imeretian mountains of Georgia, Chiatura is a monument of its past glory. Here history is often marred in legend, but what remains tells of the city’s economic and environmental decline. Chiatura is desperately trying to stay afloat in the wake of inflated communist ambitions and modern savage capitalism.

The mines are said to date back to the 1870s when the Georgian poet Akaki Tsereteli discovered the soil to be rich in manganese ore. In 1905, during the first Russian revolution, Joseph Stalin sought refuge in the city where he armed the miners and set up his now infamous racket protection ring. Consequently, Chiatura quickly became the Bolshevik stronghold in Georgia.

The German Krupp family was initially one of the main investors in the local mining industry. By 1913, the town had grown in importance and an estimated 4 000 miners worked 18-hour shifts while living in the abysmal interior of the mountains. In the summer of 1913, the miners of Chiatura organised the first strike demanding better labor conditions.

Prior to World War I, Chiatura produced almost half of the world’s manganese output. By late 1920s, the last privately-owned shares were sold to the Soviet Union. And so, under the guise of communist kitsch and pseudo egalitarian soviet industrialisation, Chiatura grew. In the 50s, the cable cars were built, and the mines expanded. Nevertheless, vulnerable to global prices the production saw a steady decline. International investment has not been able to revive the city’s economic life.

In 2006, following bankruptcy, the production was auctioned to Georgian Manganese Holding - a subsidiary to the British steel trading giant Stemcor. Consequently, Stemcor quickly sold 2/3 of the mines to the Ukrainian Private Group. The latter owned by a top Ukrainian oligarch known for his closed and non-transparent way of doing business. To date, a “privatisation agreement” with the Georgian Ministry of Economy continues to push the production up to 400 million tons annually.

It is easy to be intrigued by Chiatura. However, infatuation quickly fades as one realise the extent to which the manganese trail is riddled with debilitating injuries, broken families and lost lives. Living and working conditions in Chiatura are dismal and the environmental impact has been labeled “a disaster”. At the time of writing, none of the processing has purification plants - raising the contamination of both groundwater and the nearby Kvirila River.

To visit the mines as well as the factories in neighboring Zestaphoni is virtually impossible. A “propusk” (permit) can allegedly be obtained through a maze of offices and Kafkaesque processes which all lead to seemingly dead ends. Just days after my visit to Chiatura and Zestaphoni in 2018, yet another tunnel collapsed wounding and killing several workers.

I kept returning to Chiatura mostly to visit the people that made this essay possible. The woman managing the small hotel at the entrance of town. The worker that invited me to his home and showed me the entrances to the mines while fearing for his job and the men that out of curiosity invited me on the train. The beautiful young woman at the café in Zestaphoni that tried to get me into the factory. One can only feel humility in face of the people that live their lives in a destructive symbiosis with the ore along the manganese trail.